The British Museum and Artefacts related to the Old Testament

During our trip to London in September 2024, my wife and I set out to explore the city’s incredible historical and cultural treasures. One of the highlights was visiting the British Museum, where we specifically looked for artifacts that directly connect to the Bible’s Old Testament. In this blog, I’ll share some of the most significant pieces we encountered, along with photos and insights into their relevance. Of course, there’s far more to see and discover within the museum’s vast collections, but I hope this overview offers an enticing glimpse of the biblical echoes preserved in these ancient artifacts.

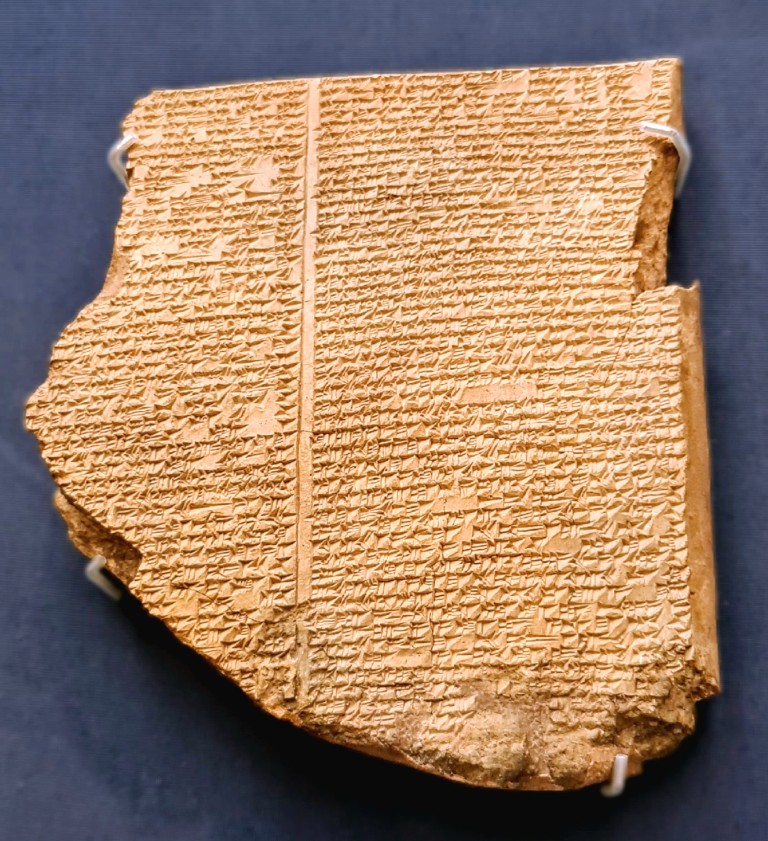

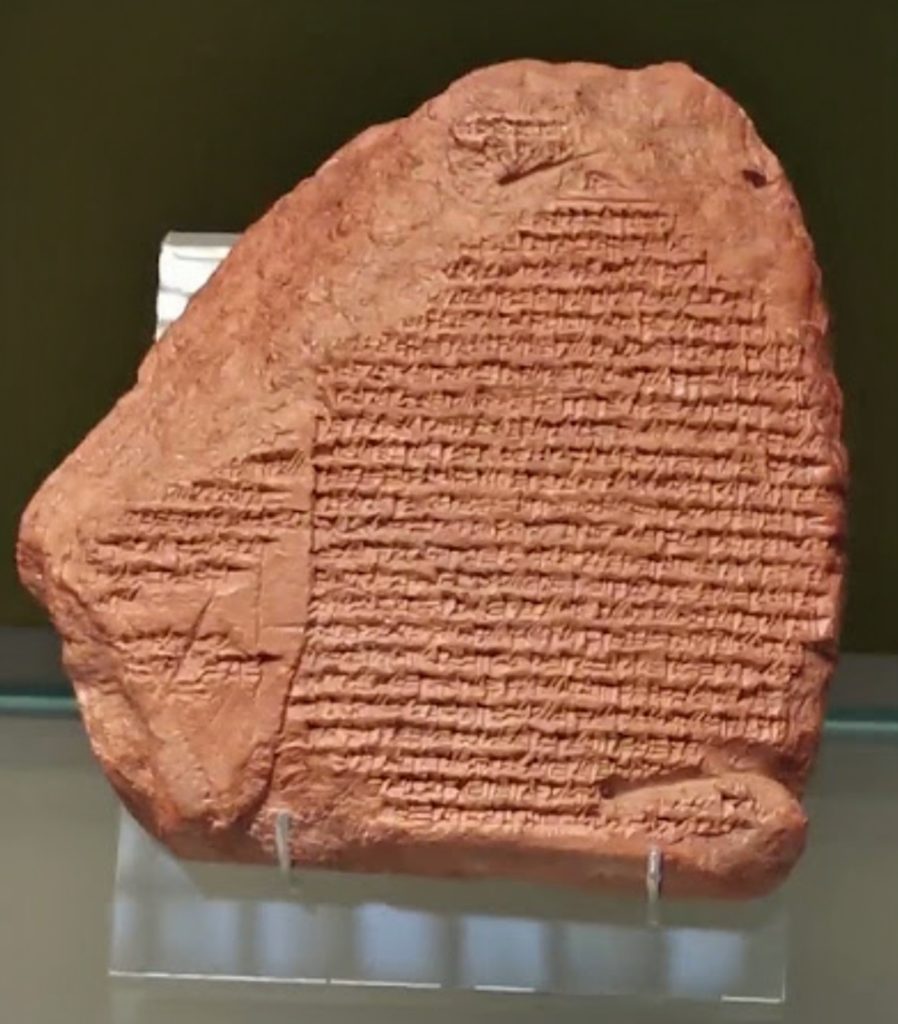

The Flood Tablet (Epic of Gilgamesh)

The Flood Tablet, housed in Room 55 (Mesopotamia), is the eleventh tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh and features a flood narrative that closely parallels the biblical story of Noah. This Mesopotamian account recounts how a great flood was divinely ordained, reflecting themes of human depravity, divine retribution, and ultimate salvation that echo Genesis 6-9. By comparing its contents with the biblical narrative, the Flood Tablet highlights the shared cultural and religious heritage of ancient civilizations and underscores the enduring motif of a cataclysmic flood across different traditions.

The Epic of Gilgamesh tablet stands as a compelling snapshot of Mesopotamian culture and literature. Unearthed among cuneiform archives, the text highlights a society grappling with themes of mortality, divinity, and the fragile relationship between humans and the forces that shape their world. Within the narrative, the protagonist’s quest for immortality and his encounter with a massive deluge underscore Mesopotamian beliefs about cosmic order and divine justice. The preservation of this tale on clay tablets testifies to a well-developed scribal tradition that profoundly influenced the region’s storytelling methods. For those studying the ancient world, the Epic of Gilgamesh offers a critical lens into the values, fears, and hopes that animated one of history’s earliest civilizations.

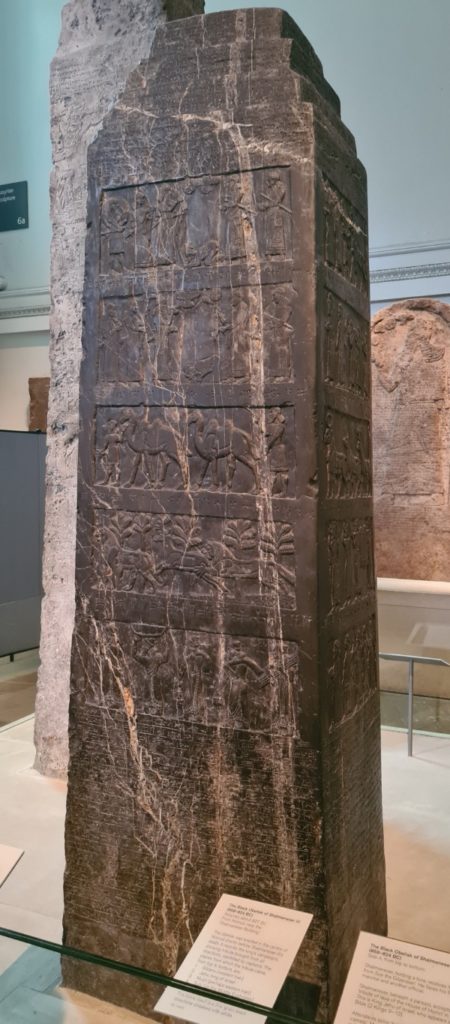

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, prominently displayed in Room 6 (Assyria), is a striking black limestone monument that commemorates the Assyrian king’s military campaigns and the tributes he received from subject rulers. Notably, it features an inscription referring to Jehu of Israel, identified in the text as “Jehu, son of Omri,” and depicts him presenting precious offerings such as silver, gold, golden vessels, and weaponry. (See focus box below) This moment captured in stone provides the earliest known visual representation of an Israelite king, which is especially significant for biblical studies because it corroborates the existence of King Jehu, whose reign is described in 2 Kings 9–10. The inclusion of detailed tribute items—“silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears”—demonstrates both the wealth of Jehu’s kingdom and the influence of Assyrian power. As a result, the Black Obelisk offers invaluable historical and archaeological insight into the intersection of Assyrian records and the biblical narrative.

In the photo below from the British Museum website, King Shalmaneser III (the third figure from the left) is shown receiving tribute from King Jehu of Israel, who is prostrating before him as the fourth figure. The two figures on the left are royal attendants of Assyria, while the two on the right serve as Assyrian officials overseeing the ceremony. The accompanying cuneiform inscription reads:

“The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received from him silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears”

The Lachish Reliefs

The Lachish Reliefs, housed in Room 10b of the British Museum’s Assyrian Sculpture collection, are a series of detailed stone panels illustrating King Sennacherib’s siege of Lachish. They vividly capture the dramatic moment when the Assyrian army overpowered this Judean stronghold, as recorded in 2 Kings 18:13–14. Not only do these reliefs offer a visual narrative of the siege, including military tactics and the subsequent deportation of captives, but they also stand as powerful archaeological evidence of an event described in the Bible. Unfortunately, during our visit, we were unable to view these historically significant pieces up close, as the exhibition area was closed to the general public at the time. Despite this setback, the Lachish Reliefs remain an invaluable window into both Assyrian warfare and the biblical story of Sennacherib’s campaign against Judah.

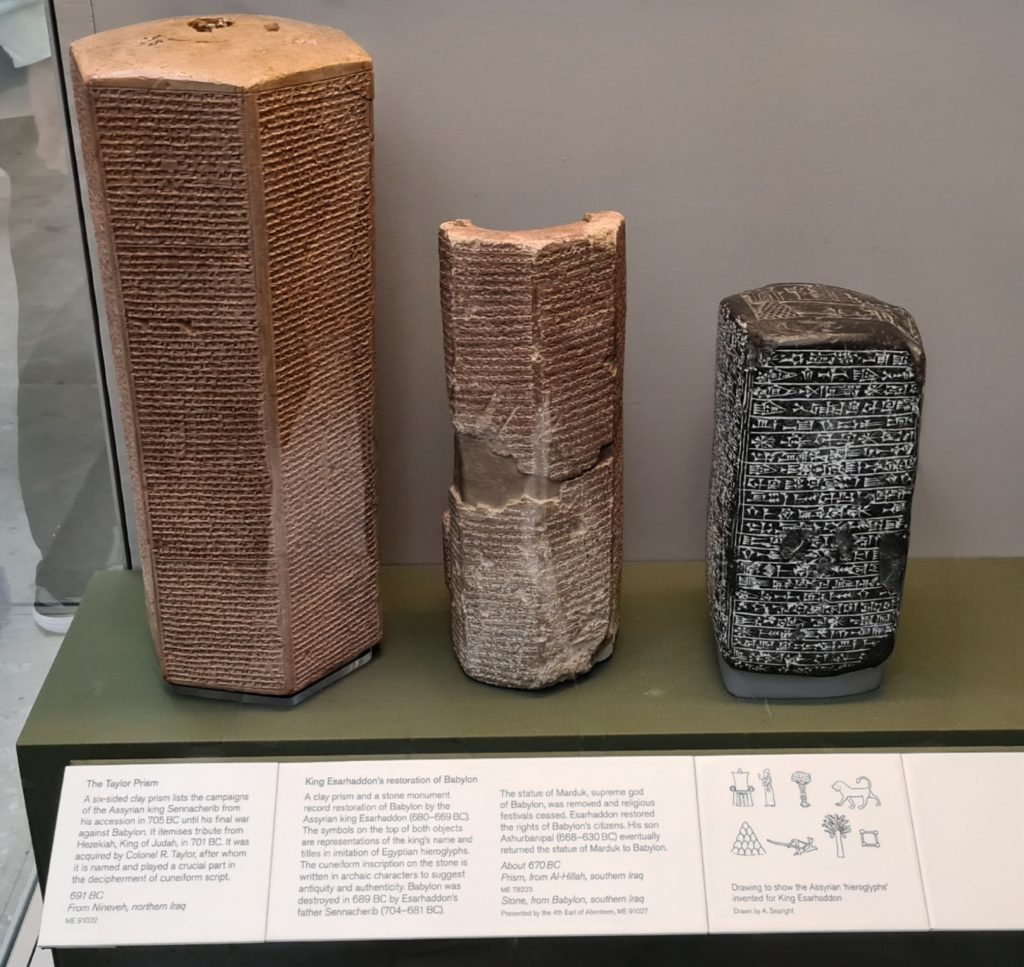

The Sennacherib Prism (Taylor Prism)

The Sennacherib Prism, also known as the Taylor Prism, is a remarkable hexagonal clay artifact displayed in Room 55 (Mesopotamia). Inscribed with King Sennacherib’s own account of his military campaigns—including the pivotal siege of Jerusalem—this document sheds light on one of the most dramatic moments in ancient history. From a biblical perspective, it aligns with the narrative found in 2 Kings 18–19 and Isaiah 36–37, verifying the Assyrian ruler’s attempts to subdue Jerusalem and his ultimate failure to capture the city. The prism thus provides a rare glimpse into how the same event was recorded by both the Assyrians and the authors of the Hebrew Scriptures, making it an indispensable piece of evidence for those interested in the interface between archaeology and the Bible.

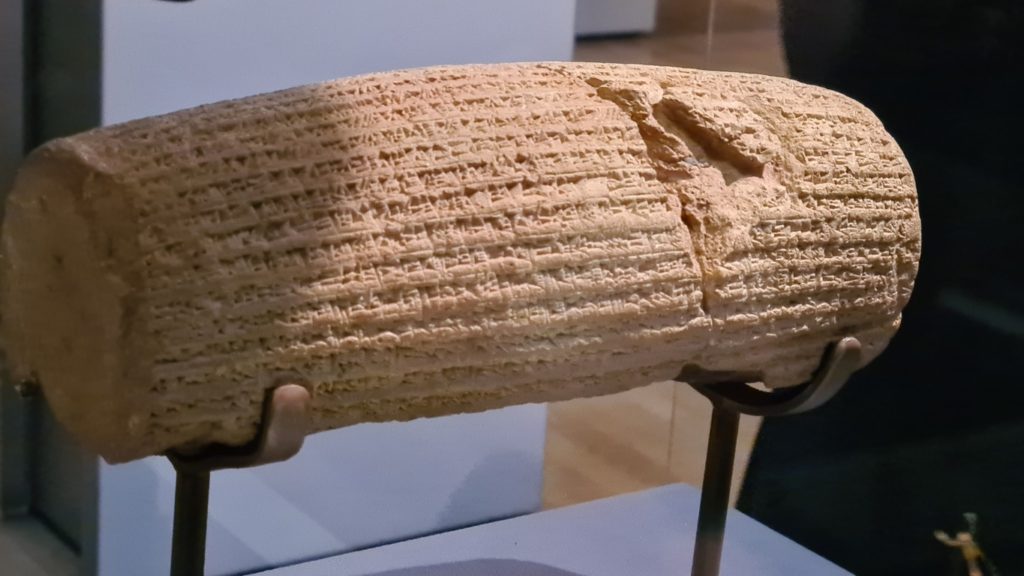

The Cyrus Cylinder

The Cyrus Cylinder, showcased in Room 52 (Ancient Iran), is a clay artifact inscribed with King Cyrus the Great’s decree allowing conquered peoples to return to their ancestral homelands and rebuild their places of worship. Its text aligns closely with the biblical record in Ezra 1:1–4 and 2 Chronicles 36:22–23, where King Cyrus grants the Jewish community permission to return to Jerusalem and reconstruct the Temple. This decree highlights Cyrus’s relatively tolerant stance toward different cultures and religions, making the cylinder a powerful bridge between archaeology and Scripture. By confirming key elements of the biblical account, the Cyrus Cylinder stands as a vital piece of evidence attesting to the historical veracity of the Persian king’s policies and the freedom he granted to various subjugated peoples.

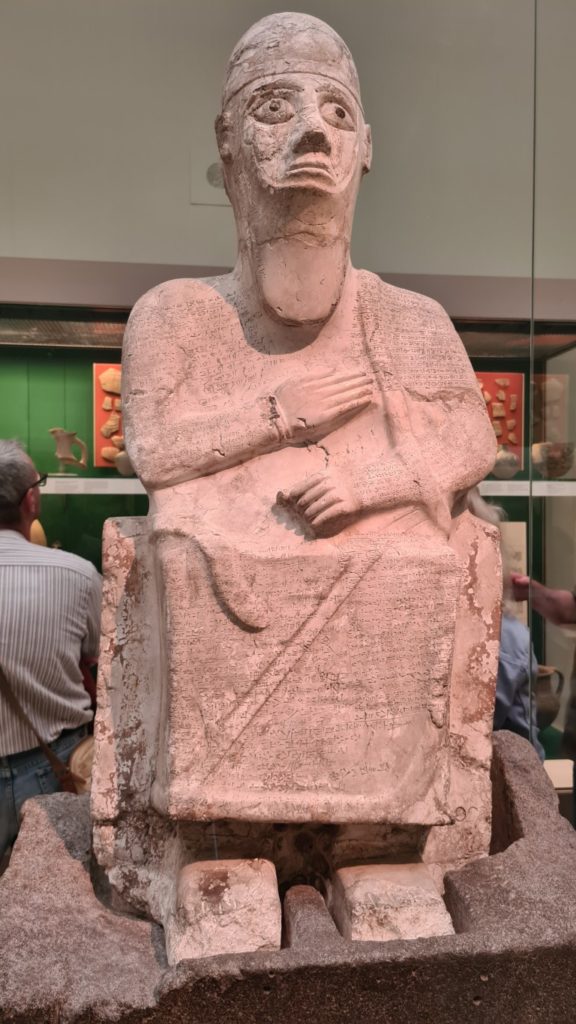

The Statue of Idrimi

The Statue of Idrimi, displayed in Room 57 (Ancient Levant), is a fascinating monument featuring a life-size representation of King Idrimi of Alalakh, accompanied by a lengthy cuneiform inscription narrating his exploits and rise to power. Although Idrimi himself does not appear in the biblical record, his reign overlaps chronologically with the period commonly associated with the Patriarchs in Genesis. The statue’s inscription provides a firsthand glimpse into the politics, diplomatic relations, and shifting alliances of the Near East during this era. As such, it helps modern viewers understand the broader sociopolitical landscape that shaped the world in which the biblical patriarchs lived, supplying vital context that enriches our reading of Genesis. This makes the Statue of Idrimi a valuable artifact for anyone seeking to comprehend the complex historical background surrounding the biblical narratives.

Ivory Panels from Nimrud

The Ivory Panels from Nimrud, showcased in Room 6 (Assyria), are a stunning example of the luxurious craftsmanship that flourished during the Neo-Assyrian period. Discovered in the ancient city of Nimrud, these intricately carved panels were originally used to adorn high-status furniture, reflecting the wealth and artistic skill of their makers. Their biblical relevance emerges in scriptural passages such as 1 Kings 10:18—where King Solomon’s throne is described as inlaid with ivory—and Amos 6:4, which references beds adorned with the same opulent material. These panels help illustrate the cultural and economic context of the ancient Near East, shedding light on the lavish lifestyles that parallel the biblical descriptions of Solomon’s palace and highlight the significance of ivory as a symbol of power and luxury.

Nimrud Ivory (personal photo from previous visit in 2015)

The Nabonidus Chronicle

Displayed in Room 55 (Mesopotamia), the Nabonidus Chronicle is a clay tablet chronicling key events during the reign of King Nabonidus of Babylon. Most notably, it documents the fall of Babylon to the Persian king Cyrus—an epoch-defining moment that set the stage for the Jewish people’s return from exile. This historical record closely aligns with the biblical narrative found in Daniel 5, which describes the demise of Babylon, and Isaiah 45:1, where Cyrus is presented as a divinely appointed agent. By situating biblical accounts alongside an official Babylonian record, the Chronicle illuminates how sacred texts and ancient historical annals converge on this pivotal transition from Babylonian to Persian rule.

The Palace Reliefs of Ashurbanipal

Located in Room 10 (Assyrian Sculpture), these stone reliefs capture the military triumphs and royal hunts of King Ashurbanipal—one of the most powerful rulers of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Beyond their artistic grandeur, these panels hold biblical resonance because Ashurbanipal is widely regarded as the “great and honorable Ashurbanipal” referenced in Ezra 4:10. By examining the meticulous scenes of battle and the king’s prowess in hunting lions, historians and biblical scholars can gain deeper insight into the identity and reign of an influential monarch who appears within the biblical narrative.

Palace Reliefs of Ashurbanipal (personal photo from previous visit in 2015)

Conclusion

All in all, our visit to the British Museum vividly showcased the dynamic interplay between archaeology and biblical history. Seeing these artifacts firsthand—from the Flood Tablet and Black Obelisk to the Cyrus Cylinder and Lachish Reliefs—underscored the profound ways in which ancient texts and material culture converge. Each object not only narrates a particular historical episode but also opens a window into the cultural, political, and spiritual worlds that shaped the biblical narrative. By standing face-to-face with these enduring remnants of antiquity, we were reminded that the Bible does not exist in isolation; rather, it is intimately connected to a rich tapestry of civilizations, each leaving tangible imprints on human history. Ultimately, these discoveries deepened our appreciation of both the Bible’s enduring stories and the meticulous scholarship that continues to illuminate them.

One can find a more detailed and thorough examination of many artifacts housed in the British Museum in T. C. Mitchell’s book, “The Bible in the British Museum: Interpreting the Evidence”, which is available for purchase at the museum’s bookshop.